Coffee is pretty much my full-time gig. Baristas know me by name, and I spend most of my days either grading papers or pretending to grade papers next to a steaming cup of coffee. I only moonlight as a teacher at a community college. It is more important that I stop by my local coffee shop to identify notes of citrus or berries in the pour over of the day while I chat with the other regulars.

But even though I particularly enjoy full-bodied Guatemalan blends, I can’t help but taste an undertone of guilt in my favorite dark roast every time I lecture on large agricultural corporations’ history of exploitation in Central America. Countries in the region were at one point coined “banana republics” for their economic dependency on agricultural exports, like bananas, to dominant foreign companies.

Because of the toll these business dealings took on both natural environments and economic stability, I could think of no better way to spend my spring break than supporting modern-day sustainable farming in Latin America. Coffee is an international commodity and coffee shops create unique social networks in cities around the world, but all of this is tarnished if the industry cannot be underpinned by sustainability.

Guatemala is a leading supplier of Arabica coffee beans, so I decided to volunteer for an eco-agriculture project near Antigua. I organized my travels through Maximo Nivel and was pleased with my placement on a local coffee farm committed to permaculture and labor rights. I was eager to become a part of not only organic coffee production, but also a meaningful cultural and ecological project.

Agriculture is a particularly large employment sector in Central and South America, and Guatemala’s developing economy is substantially supported by coffee exports. However, production numbers are often valued over sustainable practices. This is why NGOs have popped up throughout the country to merge traditional farming techniques with environmentally conscious and humane farming operations.

Supporting international industries does not need to come at the expense of the local communities that house production. The farm I volunteered on was 100 percent pesticide-free and integrated into the surrounding community. Rather than working for a foreign employer, I was working alongside local farmers to root out any threats mass coffee production could have on the natural environment or indigenous population.

In addition to growing eco-friendly crops, the farm also emphasized the importance of humane workplace standards. Without widespread recognition of labor unions or industry regulations, agricultural workers in developing economies are exploited time and again. Responsible farming also means more field hands and less mechanization, so agricultural NGOs are always in need of volunteers.

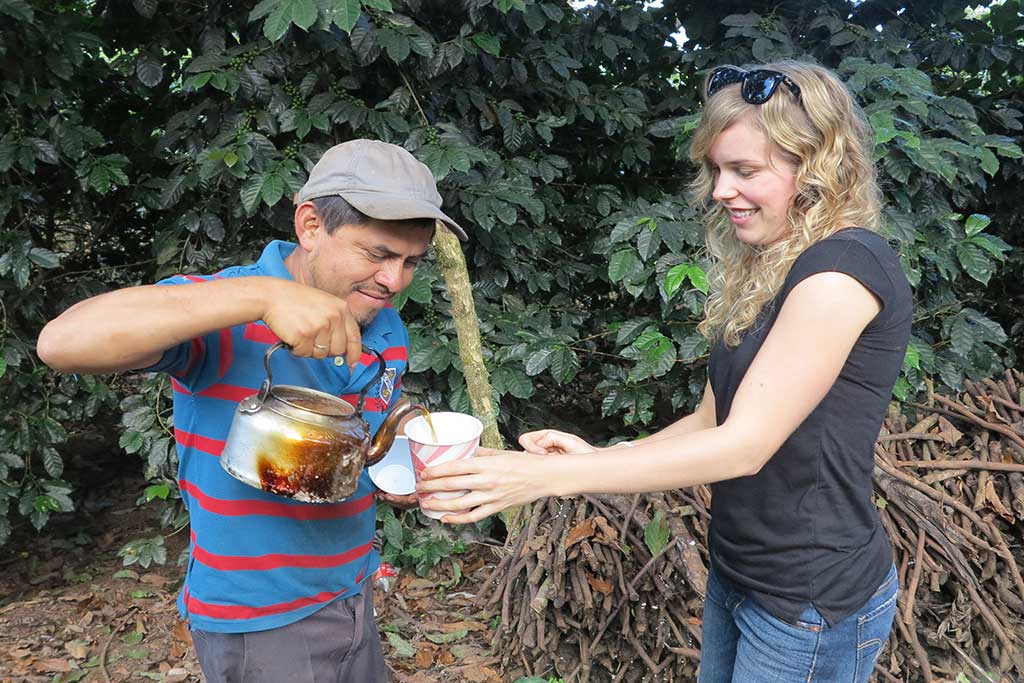

I was happy to spend a few weeks working on the farm, and to see that I was meeting an actual need. I got to participate in the spring harvest. As they picked the coffee cherries to be dried and sent off to roasters, I was able to assist with different stages of the process including picking, processing and packaging. I also did some weeding and general maintenance around the growing grounds.

I was fortunate to work with Guatemalan farmers who knew so much about the trade. I had done a lot more coffee drinking than manual labor in my life and was appreciative that they were very patient in training me. Each task is an important part of preparing the beans for local and international sales.

It was very fulfilling to be involved in an agricultural operation that is mindful of its ecological and socio-economic impact. Long-term local farming is aimed at sustaining the economy rather than temporarily inflating it. Because it is run responsibly, the coffee farm should be able to keep serving future generations of its own community, as well as the outside world.

The specialty coffee industry goes hand in hand with Antigua’s reputation as a tourist destination. There is a demand for high-quality coffee both close by and across the globe. If processes continue to be developed consciously, each link of the coffee production chain will benefit—from farmers and roasters to coffee shops and kitchen tables.

It is beautiful to see the balance that can result from industries that complement their natural settings. Each country has a different landscape to draw from, and as the international population grows over time, it is especially important to harness rather than destroy our limited natural resources. High altitudes, sunny skies, ample rainfall, and rich volcanic soil are all agricultural advantages.

Guatemala is home to many microclimates that can support the growth of coffee trees. I hope more and more farmers can responsibly capitalize on these tools rather than depleting the natural environment and mistreating local work forces. Though it was only for a short time, I was grateful to shift to a different daily grind and play a small role in something sustainable.