“So, what are your plans for the summer?” If you’re young enough, any answer to this question is met with a smile. “I might go to the beach.” “I just got my first library card.” “I’ll be perfecting my cartwheel.” All acceptable answers. But the summer before your last year of college that question takes on an ominously leading tone. I was on the precipice of having to find full-time work, and I wanted to dedicate my weeks off to a project that was professionally meaningful.

Because I was on track to graduate with a degree in elementary education and Spanish, I started looking for a teaching internship. When I found Maximo Nivel, I knew it would be a good fit. They offer a variety of education internships at bilingual schools in Latin America. And though I hadn’t been specifically looking for opportunities abroad, I knew interning in another country would put my instructional and linguistic skills to the test, as well as giving my resume a competitive edge.

Teaching abroad is also the ideal way to gain a more global perspective both in and out of the classroom. So, I got in touch with the Maximo staff to discuss which program would be best for me. And before I knew it, I had an answer to the summer question: “I’ll be interning at a private bilingual school in Cusco, Peru.” I had found an answer that I was confident in—an answer that aligned with my professional goals and gave me an opportunity to experience South America!

I spent eight weeks working alongside full-time teachers, creating my own lessons, and learning from my own mistakes. I taught in a second grade and a fifth-grade classroom throughout my internship, as well as helping with school-wide activities. I already had a lot of experience with lesson planning and curriculum alignment. However, spending more time in a school setting turned out to be the missing link. Lesson planning for hypothetical levels and learning needs is very different from the real thing.

By delivering lessons to actual students, I was able to see firsthand what worked and what didn’t. This practical experience was also reinforced by observations and constructive feedback. I made so much progress in how I was delivering material because I was receiving relevant guidance about what I could improve. I also learned a lot from the educational philosophy of the school I worked at, which focused heavily on the thinking process over mere memorization.

Public schools in Peru are regularly underfunded and overcrowded. Due to these systemic shortcomings, the private education sector is a quickly growing alternative to public schools that is helping to close gaps in both quality and accessibility. I was fortunate to be placed in a private school with a very progressive teaching methodology. Both the learning environment and the curriculum itself were geared towards the development of well-rounded citizens.

Teachers intentionally integrated emotional and social education into standardized academic subjects. Rather than focusing on consequences for misbehavior, the entire culture of the school emphasized student-centered learning. By prioritizing students’ engagement in their own education, teachers were often able to prevent, rather than respond to, behavioral concerns. Dated instructional models built on committing information to memory still encumber Peruvian public schools. By contrast, the teachers I worked with valued thinking above all else.

If students develop healthy critical thinking patterns, they can apply this skill set to any new concept. But what does analytical thinking look like at an elementary school level? Before my time in Cusco, I wouldn’t have considered open conversation an essential (or even realistic) part of primary education. The lower grades had always seemed pretty straightforward to me. However, I had failed to recognize that teaching students how to form, process and communicate their own ideas is just as important as their ABCs and 123s.

The teachers I worked with expertly modeled active learning. Their students were constantly immersed in their own education and were therefore very motivated to participate. These students are building a foundation of cognitive skills that will shape the rest of their lives. And introducing mindful habits—such as metacognition, self-reflection and innovative problem solving—starts with one simple question. The students were constantly encouraged to consider why they were doing what they were doing. Therefore, the school culture valued task-based learning over more traditional assessment models.

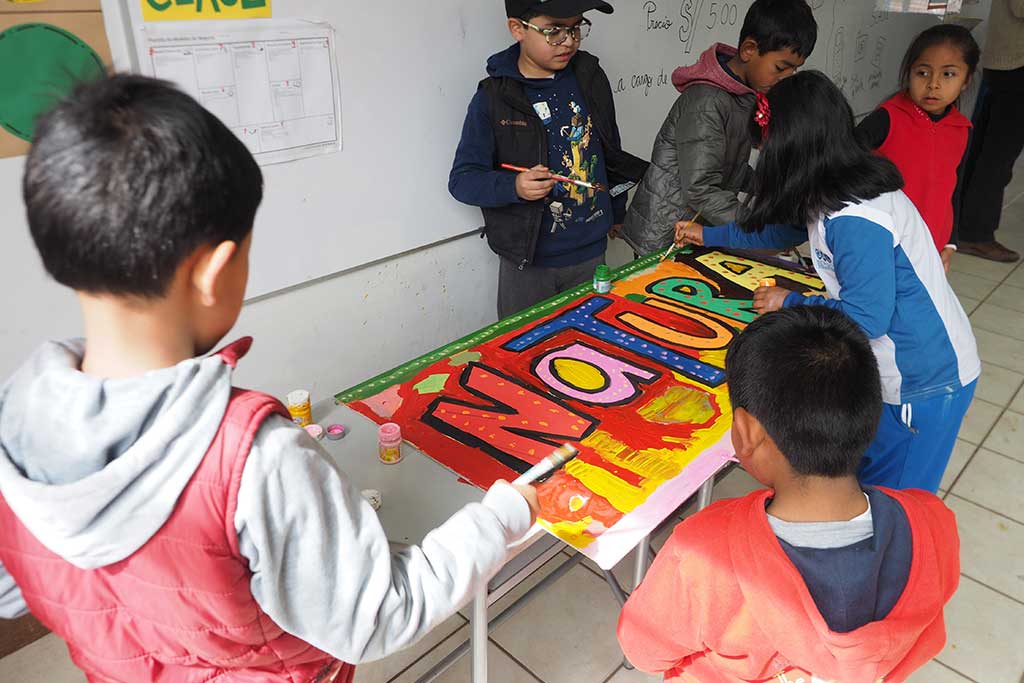

Before seeing how this worked hands on, I might have criticized project-based learning for being less academically rigorous than traditional testing. However, applying learning to real-world situations proved very valuable. Students as young as six years old were pushed to think creatively, critically, and contemplatively. The school put on monthly educational workshops to facilitate applied learning. For example, students from all grades worked together to organize a business fair in which they showcased their own startup ideas.

Activities like this showed me the potential everyday education must be immersive, experiential and practical. Teaching students to think for themselves is teaching them to be ready for the real world. The school I worked at did a phenomenal job of melding national curricula, Cusqueñean culture and innovative teaching strategies into a viable educational model. I have left behind the misconception that real learning has to involve high pressure exams, pop quizzes, and timed essay writing.

My teaching internship altered my previous (mis)conceptions about alternative forms of learning, and the experience I had in Cusco will definitely change how I run my future classroom. If students can sit down in a “thinking circle” at seven years old and explore why they show up to school every day, who knows what they’ll be able to communicate and accomplish by the time they’re my age!